Which language came first is a question that does not have a single agreed answer. The idea of identifying the oldest language in the world depends on how scholars define and interpret historical evidence. More than 7,000 languages are spoken in the world today, and each has a history that stretches back through centuries of change.

Some languages have written records that go back thousands of years, while others survived only through speech until much later. Because speech predates writing by tens of thousands of years, determining the oldest language in the world depends on the type of evidence used to define “oldest.”

In this article we will explain the main approaches scholars use and identify the languages that qualify under each one.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Short Answer: It Depends on What “Oldest” Means

There is no confirmed first human language, and therefore no single, universally accepted answer to what the oldest language in the world actually is. The oldest language depends on the type of evidence used. Below are the main categories scholars rely on:

1. Oldest deciphered written languages

These are the earliest languages preserved in readable inscriptions.

2. Oldest languages still spoken today

These languages are often mentioned in debates about the oldest language in the world because they combine ancient origins with documented continuity.

3. Oldest major language families

These represent deeper ancestry than individual languages.

4. First spoken language

Unknown. Speech predates writing by tens of thousands of years, and no direct evidence survives.

From our perspective as a translation agency, the idea of a single “first language” is not supported by evidence. The historical record shows only the languages that were written early enough to survive, such as Sumerian, Egyptian and Akkadian.

Other languages remain old through continuous use, including Greek, Chinese, Tamil and Hebrew, while major language families reach even farther back. The earliest spoken language remains unknown because speech existed long before writing. In practice, the concept of the “oldest language” depends entirely on the criteria used, not on a single historical origin point.

How We Identify the Oldest Language

Scholars rely on evidence that can be documented or reconstructed. Spoken language leaves no trace, so researchers use several methods to determine how far back a language can be traced.

Key Methods Used by Researchers

- Archaeological records

Written inscriptions on durable materials such as clay, stone or bone provide the earliest verifiable evidence of specific languages. - Historical linguistics

Changes in grammar, sounds and vocabulary help identify when one language diverged from an earlier stage or related variety. - Comparative reconstruction

Linguists compare related languages to infer features of older, unattested languages such as Proto-Indo-European or Proto-Dravidian. - Mutual intelligibility

When speakers of two varieties can no longer understand each other, those varieties are treated as separate languages rather than dialects.

These methods allow scholars to determine when a language becomes identifiable in the record, but they cannot reveal the earliest spoken languages.

Oldest Written Languages Ever Recorded

The earliest languages we can verify are those preserved in readable writing systems, and they are often cited in discussions about the oldest language in the world. These inscriptions survived because they were created on durable materials such as clay and stone. The languages below represent the oldest deciphered written records known today.

1. Sumerian

Earliest cuneiform tablets appear around 3200 BCE in Mesopotamia. These texts document administration, trade and early literature.

2. Egyptian

Hieroglyphic writing dates to roughly 3200 to 3000 BCE. The earliest complete sentence appears on the tomb of Pharaoh Seth-Peribsen.

3. Akkadian

Attested from around 2400 BCE, written in cuneiform. It became the administrative and diplomatic language of Mesopotamia for many centuries.

Summary Table: Early Written Languages

| Language | Approximate Earliest Date | Writing System | Region |

| Sumerian | c. 3200 BCE | Cuneiform | Mesopotamia |

| Egyptian | c. 3200 to 3000 BCE | Hieroglyphs | Nile Valley |

| Akkadian | c. 2400 BCE | Cuneiform | Mesopotamia |

These languages represent the earliest readable evidence for human linguistic activity.

Ancient Languages That Did Not Disappear Completely

Some ancient languages no longer function as everyday spoken languages but survive through descendants or restricted use. These languages remain important because they link modern speech to early historical records.

Egyptian through Coptic

Ancient Egyptian is no longer spoken conversationally, but its descendant, Coptic, survives as the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox and Coptic Catholic churches.

Latin through the Romance languages

Latin is no longer used as a native language, yet it continues through Italian, Spanish, French, Portuguese, Romanian and other Romance languages.

Akkadian through related Semitic languages

Akkadian itself is extinct, but its linguistic lineage continues within the broader Semitic family, which includes Arabic, Aramaic and Hebrew.

Sanskrit in religious and scholarly use

Sanskrit is not used as a first language today, but it remains active in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain traditions, and in academic study.

These examples show that a language can disappear from daily communication yet remain influential through descendants, liturgical roles or scholarly preservation.

Oldest Languages Still Spoken Today

These languages have ancient roots and remain in active use. Their modern forms have changed over time, but each maintains a traceable connection to early written or historical evidence.

Greek

Documented since the Mycenaean period around 1450 BCE. Modern Greek is a direct descendant and is spoken by millions today.

Chinese

Old Chinese appears in oracle bone inscriptions from about 1250 BCE. Modern varieties, including Mandarin and Cantonese, descend from this early stage.

Tamil

Attested in inscriptions and early literature dating to at least 300 BCE. Tamil remains a first language for tens of millions of speakers.

Hebrew

First recorded around 1000 BCE. After a long period as a literary and liturgical language, Hebrew was revived in the 19th and 20th centuries and is now spoken natively.

Aramaic

Attested from around 1100 BCE. Modern forms of Aramaic survive among communities in the Middle East and the global diaspora.

Farsi (Persian)

Descends from Old Persian, recorded between 522 and 486 BCE. Modern Farsi remains widely spoken in Iran and surrounding regions.

Summary Table: Longest Continuously Attested Living Languages

| Language | Earliest Evidence | Current Status |

| Greek | c. 1450 BCE | Native language |

| Chinese | c. 1250 BCE | Native language (multiple varieties) |

| Tamil | c. 300 BCE | Native language |

| Hebrew | c. 1000 BCE | Revived native language |

| Aramaic | c. 1100 BCE | Limited native communities |

| Farsi | c. 522 BCE | Native language |

These languages maintain a direct line of continuity from ancient times to the present.

Classical Languages That Influenced Modern Speech

Some ancient languages are no longer used as native, everyday languages but remain influential through religious tradition, literature or their role as ancestors of major modern languages.

Sanskrit

Earliest texts date to around 1500 BCE. While not spoken natively today, Sanskrit remains active in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain practices and is widely studied in academic contexts.

Latin

The language of the Roman Republic and Roman Empire. Although no longer spoken as a native language, Latin directly shaped the Romance languages and continues in scientific, legal and religious terminology.

Classical Chinese

Used for administration, scholarship and literature for more than two millennia. Modern Chinese languages developed from earlier forms but differ significantly from Classical Chinese.

Coptic

The final stage of the Egyptian language. Today it is used primarily in liturgy within the Coptic Church.

Pali

Associated with early Buddhist scripture. No longer a native language but still used in religious contexts and scholarly study.

These classical languages shaped modern linguistic systems and cultural traditions even after their use as everyday spoken languages declined.

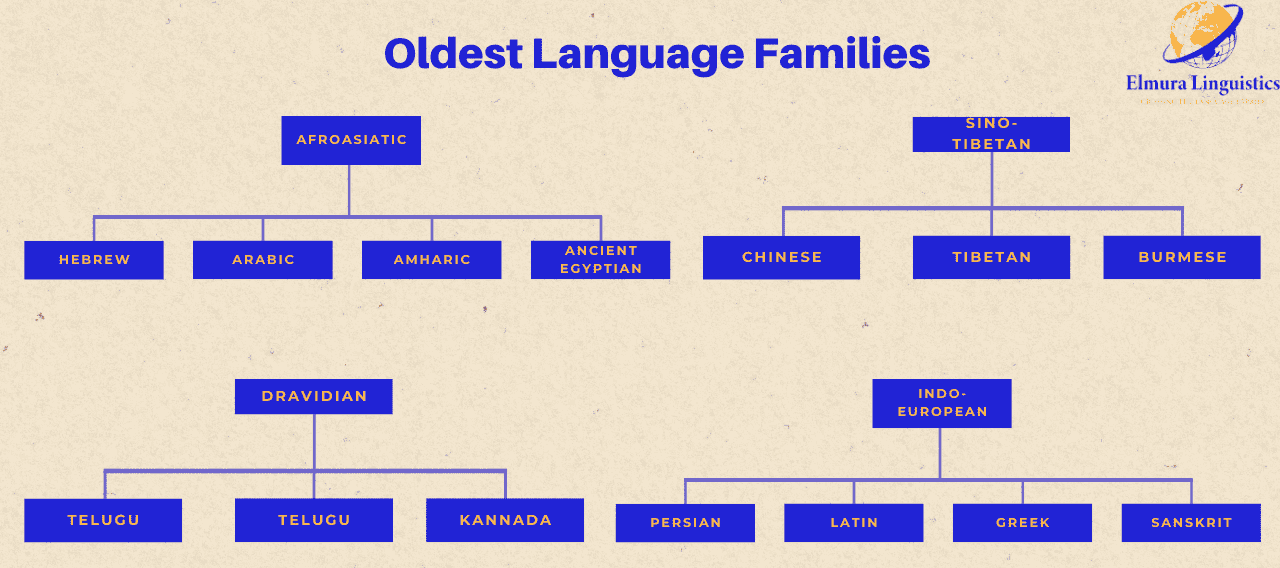

Oldest Language Families

Language families consist of languages that descend from a shared ancestral source. For most families, this ancestral language was never written and is known only through linguistic reconstruction. Scholars identify these ancestors by comparing vocabulary, sound patterns and grammatical features across related languages.

Dates assigned to these proto-languages are approximate because they rely on reconstruction rather than direct historical records.

Afroasiatic

Includes Arabic, Hebrew, Amharic, Berber languages and ancient Egyptian. Often cited as one of the oldest large families because several branches have very early written records.

Indo-European

Includes English, Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, Persian and many European and South Asian languages. Reconstructed ancestral forms point to deep historical roots.

Dravidian

Includes Tamil, Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam. Thought to predate many early Indo-European languages in South Asia.

Sino-Tibetan

Includes Chinese, Tibetan and Burmese. Early inscriptions in Old Chinese support its long historical depth.

These families represent the deepest levels of linguistic ancestry that can be reconstructed with current evidence.

The Debate Over Which Language Came First

Different groups highlight different languages as the earliest because the answer depends on the type of evidence used. Each claim reflects a specific interpretation of history rather than a definitive starting point. Much of the debate about the oldest language in the world exists because different criteria produce different answers.

Claims Based on Written Evidence

Supporters of Sumerian or Egyptian point to the earliest deciphered inscriptions. These records are among the oldest that can be verified through archaeology.

Claims Based on Continuous Use

Greek, Chinese, Tamil and Hebrew are often proposed as the oldest because each has a long, traceable tradition that continues in modern speech or revived use.

Claims Based on Cultural or Literary Tradition

Sanskrit and Classical Chinese are highlighted for their early texts and influence on religion, philosophy and literature, even though neither represents the first spoken language.

Claims Based on Reconstructed Ancestry

Some arguments focus on language families such as Afroasiatic or Dravidian. These families may extend deeper into prehistory than the earliest written languages, but their dating relies on linguistic reconstruction rather than physical evidence.

The discussion persists because each method highlights a different aspect of language history. No single approach identifies one definitive first language.

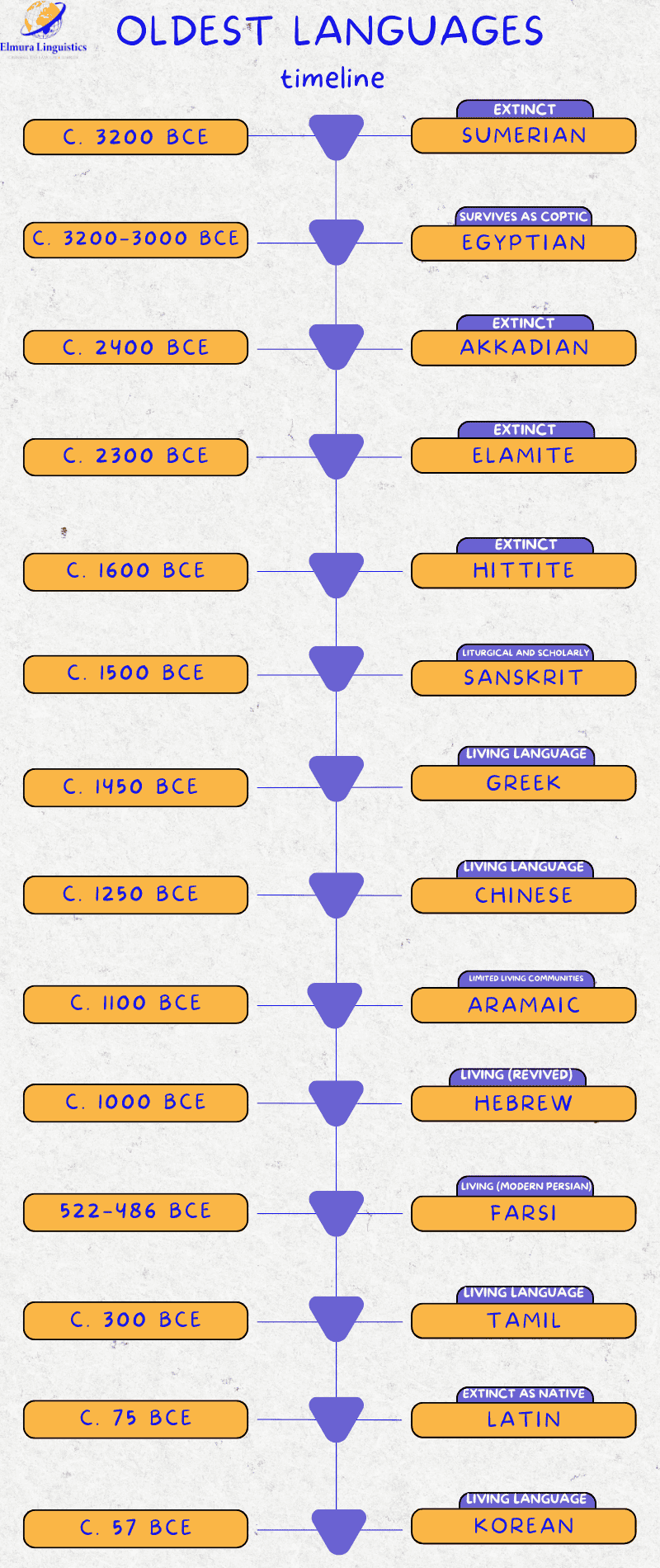

Timeline Snapshot of the Oldest Languages

This section provides a simple chronological overview of key ancient languages based on their earliest known evidence. Dates represent the oldest widely accepted attestations.

The timeline shows that several ancient languages appear within a few centuries of one another in the written record. Some survived through descendants or revival, while others remained in continuous use.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the question of the oldest language in the world has no single definitive answer, because language history depends on written evidence, cultural continuity, and linguistic reconstruction.

The languages in this table represent the earliest verifiable stages of human linguistic history. Their dates come from written records, archaeological evidence or well-established linguistic research. While each language follows its own path, together they show how writing, cultural continuity and linguistic reconstruction allow us to trace language histories across thousands of years.